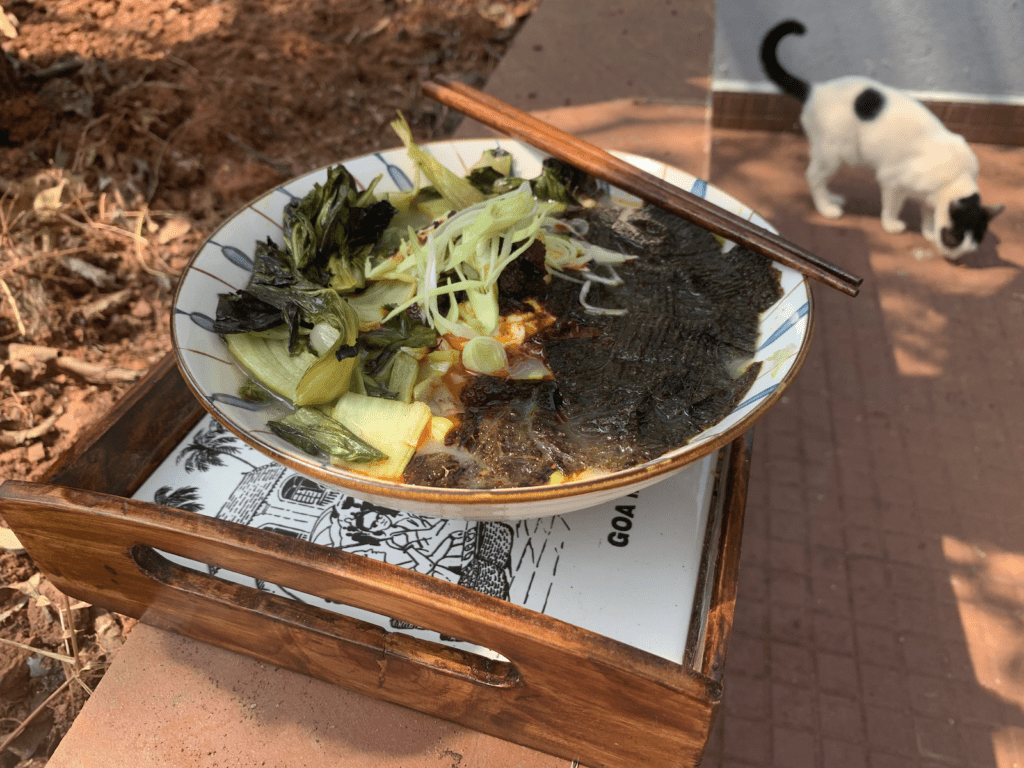

Last week I began work on a ramen using local ingredients from Goa. I swapped the popular pork topping for a spicy Goan sausage called Choris with blended cashew nuts as a base for the broth. The further I strayed from a traditional bowl of ramen, the more I’d question what makes ramen ramen?

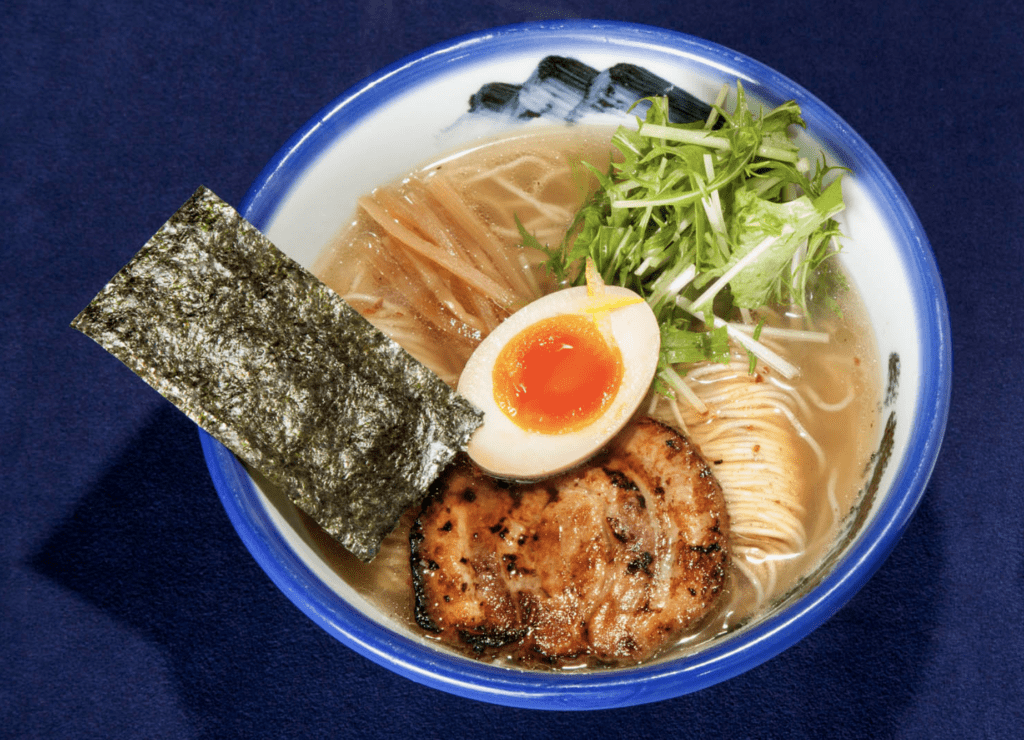

The key distinction is that ramen noodles are made with alkaline salts, making them chewier than most other noodles. That said, ramen has five components: noodles, broth, tare (seasoning mixture), aromatic oil, and toppings. The alkaline noodle and broth components are non-negotiable, whereas there’s more flexibility with the remaining 3 components.

For example, high-alkaline pasta bolognese wouldn’t count as ramen. Without broth, no ramen. The difference between a noodle soup and ramen is the alkaline content of the noodles. On the other hand, if someone forgets to add aromatic oil to traditional ramen, it would not cease to be ramen.

There is immense regional variation in ramen making, and plenty of interpretation around balancing the tare, oils, and toppings. The fact that there are no rules and ramen is still evolving is part of what makes it so interesting.

Where exactly does ramen come from?

The history of ramen is messy. The most plausible theory is that ramen comes from China and was introduced to Japan in the late 19th century. The idea of putting noodles in broth wasn’t new to Japan, but this particularly springy noodle in a chicken broth was introduced by Chinese merchants in Yokohama, the first Japanese port opened up to foreign trade in 1859.

Ramen wasn’t that popular for its first 50 or so years in Japan. It was street food, popular with blue-collar workers and foreigners. That all changed when the Japanese lost World War II. A devastating rice harvest, the worst in 42 years, led to the US flooding Japan’s market with cheap wheat to deal with the food shortage. The abundance of wheat saw ramen explode in popularity as a cheap and filling meal.

The instant ramen noodle was invented in 1950s, either by Momofuku Ando (the founder of Nissin Foods) or a company named Matsuda Sangyō. This one invention meant that anyone in the world could make ramen by adding hot water. Instant noodles began to make their way around the globe as everyone’s favorite, ultra-convenient, comfort food.

According to ‘Ramen Obsession’ by Naomi Imatome-Yun, the real ramen boom didn’t happen till the 1990s. Ohsaki-san, Japan’s preeminent ramen critic, cites 1996 as a turning point: “The Internet started. Customers began putting images of ramen on the Internet. Before that, a ramen maker could visit different ramen shops and just steal their techniques. After 1996, you could see if one ramen shop was a copy of another. Ramen shops had to start developing original styles.”

With its adoption, ramen became an intensely regional phenomenon in Japan. Each locality accentuates ramen with its own history and the best of its local ingredients. For example, Hiroshma has a fiery adaptation where the noodles are served separately from the spicy sauce.

Tokyo shoyu ramen is what most people picture when they think of ramen. Tokyo-style ramen is distinctive because the broth is made with dashi, a broth made with dried fish flakes and kelp.

Hokkaido is the birthplace of Sapporo-style miso ramen. A blended pork bone marrow and chicken stock, flavored with miso, and a fine layer of oil to prevent the heat from escaping during harsh winters.

What is traditional ramen?

There is no such thing. Ramen has roots in a Chinese noodle soup, but it has become distinctly Japanese, with a world of regional variations.

From a practical viewpoint, if you’re learning to make ramen (like I am), you can bucket ramen into three main flavors based on the type of tare used. Tare means ‘sauce’ in Japanese, it’s not specific to ramen. Think of tare as a concentrated flavoring agent that adds to the broth, since broth doesn’t typically have much seasoning.

- Shio – Shio tares are pale and clear, and the taste comes from using lots of salt.

- Shōyu – Shōyu tare comes from a soy sauce base, and it’s still clear but much darker

- Miso – Rather than using salt or soy sauce as the base, some ramens use miso for flavor.

These are loose categories. Some bowls combine all three flavors, and others wouldn’t fit into any of these groupings. Ramen is unique in that there is lots of room for creativity. The fact that it is a relatively new form of food and is unencumbered by years of tradition is part of its global appeal.

Where is ramen heading?

Universal familiarity with exported instant ramen noodles set the stage for ramen’s current global appeal.

Outside of junk food, the international ramen boom started in 2004 and can be traced back to the Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York City. Given that the noodles originally came from China and were adopted by every region in Japan. It’s only fair that other countries incorporate their own culinary influences into ramen and adapt it to their own climates, ingredients, and tastes.

Naomi Imatome-Yun’s “Ramen Obsession” highlights a popular Colorado ramen shop’s bowl with confit duck, arugula, and apples.

Hawaii has ramen with black garlic oil, garlic butter, and Parmesan cheese.

Chef Gregg Des Rosier even has Milwaukee-style ramen with seared flank steak and smoked bone marrow butter.

Bone marrow butter and parmesan on ramen might feel wrong, but as Naomi Imatome-Yun points out, it fulfills two important elements: It’s distinctly regional and uses local ingredients.

If alkaline noodles, broth, and incorporating your own culinary influences and using local ingredients makes ramen ramen, as a foreigner who lives in Goa, what could pay more respect to the spirit of ramen than a Choris ramen with a cashew nut cream and coconut vinegar?

Done. I had my answer. I knew what ramen was all about.

- Alkaline noodles.

- Broth

- Use local ingredients

Then I stumbled into a type of ramen called Mazenmen. It has very little broth in the bowl. It’s practically a dry noodle. But it’s definitely considered a type of ramen.

Things got worse. I discovered abura soba, a completely brothless ramen.

What is going on?

To confuse the whole situation further, I was eating ramen with a friend who’d actually been to japan the other night. His understanding was the thing that really makes ramen is the fat. I was skeptical to say the least. Sure, he’d been to japan, but I’d been reading up on the subject.

Then earlier this week, I’m in bed reading Ivan Orkin’s masterpiece, and I find this…

So it looks like I’m back to square one.

I have no idea what makes ramen ramen.

(╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

The key distinction is that Ramen noodles are made with alkaline salts, making them chewier than most other noodles. That said, ramen has five components: noodles, broth, tare (seasoning mixture), aromatic oil, and toppings. The alkaline noodle and broth components are non-negotiable, whereas there’s flexibility with the remaining 3 components.